In the world of Foxtail Pines

By Tom Killion

Whitney Crest from Kaweah Basin

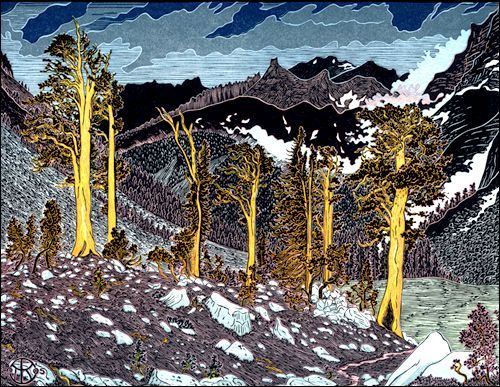

Big Arroyo, Foxtail Pines

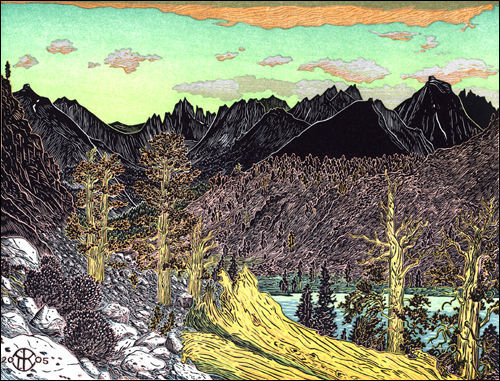

Sawtooth Crest from Chagoopa Creek

Tom created these three views of Foxtail Pines to be arranged as a triptych. They are all sold out now.

A few summers ago I took a backpack trip through the world of Foxtail Pines, circling the Kaweah massif in the southern Sierra Nevada of California. I set off from the Giant Forest in Sequoia National Park with two friends, Donna and Julie, and hiked up the High Sierra trail, camping along the way at appropriately named Bear Paw Meadow. After a night of "bear-a-noia" under dark firs, we hit the morning trail and quickly found ourselves in the airy world of the High Sierra, following a rock-cut, precipitous path past Valhalla Canyon and spectacular Hamilton Lake, up and ever up to ice-bound Precipice Lake amidst thunder, lightning and hail-laced rain. Finally, after a last, positively "Scottish" section of heather-fringed boulders, bubbling freshets and green swards, we crossed Kaweah Gap and descended into the World of Foxtail Pines.

Big Arroyo, Foxtail Pines

Foxtails are cousins of the better-known bristlecones, the oldest living trees, which inhabit the White Mountains just a score or so miles due east of the Kaweah range. Some foxtails are estimated to live up to 2,500 years, and core samples from fallen logs have been dated to over 4,000 years ago. Unlike bristlecones, the foxtails form real high altitude forests on the plateaus of the Southern Sierra above 9,000 feet, while "ghost forests" of long-dead foxtails, dating from warmer eras in the distant past, cling to rock slopes and ridges in places up to almost 12,000 feet. With their huge trunks, worn by centuries of wind-driven ice to a glowing golden color, the foxtails are by far the largest and most impressive living things in their high altitude environment. At the top of Big Arroyo, as threatening clouds closed in, we came across a stand of foxtails glowing orangey-yellow in the last sunset light. I stopped to sketch until the first raindrops wet my tablet and my fingers numbed, then I hurried down to a hastily-pitched camp amid wet brush and scrubby lodgepoles, eating supper in the dark between spats of rain.

The sun dried our gear and bounced us up the trail the next morning as we climbed onto Chagoopa Plateau. In the afternoon we reached a creek junction in a long green meadow below the towering red-gold mass of Kaweah Peak. Here we set off cross-country, following Chagoopa Creek up through bogs and boulders, swatting mosquitoes among the remnants of an old forest fire, until the creek narrowed to a deep freshet flowing between green verges fringed with corn lilies. On either side of the creek was a dry, sandy plateau forested with foxtails and lodgepoles. We camped amid giant orange-yellow trunks on pure white sand. The next day my companions climbed Kaweah Peak while I wandered this dry 10,000 foot elevation forest of widely spaced trees, listening to nothing but the creek bubble and the breeze in the pine branches, feeling how fortunate I was to be in this ancient mountain Foxtail World.

Sawtooth Crest from Chagoopa Creek

The following morning we continued up the creek to Kaweah Pass, the cross-country notch leading into the desolate fastness of Kaweah Basin. I stopped to sketch a westward morning view of the Sawtooth Crest from beside the creek, then continued up through a ghost forest of ancient golden tree trunks clinging to boulders whose crevices sprouted pale columbines and pink pentstemons. Finally, we scrambled up a boulder gully, looking for the little lake at the top. We found it, electric blue and full of floating ice under the towering granite of Kaweah Peak. A difficult traverse around the lake brought us to a notch leading down through sliding talus to a chute in the first band of vertical rock. We descended one at a time, then together for thousands of feet down to a second cliff band which we traversed looking for a route. Donna found one and soon we were off the rock onto a snow field. A short glissade landed us on the greensward between two lakes, where we lunched amid spattering rain. Clouds darkened behind the towering black pinnacles of the Kaweahs as we headed a few miles further down-valley, tired and sore, to camp in another foxtail forest above the last lake of the basin.

No fish inhabited any of the lakes or streams in the basin. The outlets all fell away thousands of feet over waterfalls and cataracts into the canyon of the Kern, and no trails of any kind led into the basin, so it was never stocked. After a night of spectacular lightning along the Whitney Range across the canyon, we packed our wet gear and set out through a low pass leading north into the Picket Guard drainage. Climbing the south slope we passed through another foxtail forest scattered with immense golden logs that might have fallen around the birth of Christ. I stopped to draw the pinnacles of Whitney Crest, Russell, Tunnabora and Barnard under lowering clouds, then caught up with the ladies as they hiked down Picket Creek. We skirted a deep green lake in light rain, then clambered over its rock rim to descend slippery granite thousands of feet into the Kern-Kaweah canyon. Here we lunched and parted company, my friends heading east to Junction Meadow and Shepherds Pass, while I walked alone up the rainy Kern-Kaweah.

Whitney Crest from Kaweah Basin

I had enough food for two days, and planned to climb over the Great Western Divide through a notch known as Pants Pass leading from the head of the Kern-Kaweah into Nine Lakes Basin. On the map it looked doable from the east, but the western face fell a thousand feet through tightly-spaced contours. If I couldn't get over it with my broken frame pack, bad knee and blisters (by now I was hiking in sandals and leaning on a stick I picked-up along the trail), I would have to return over the equally arduous, but far longer, route we took into Kaweah Basin. We had seen no one since we left Big Arroyo four days before, and I met no one on the faint trail up the canyon. My only companion was a black bear I saw among the downed timber of a recent avalanche. Where the river took a lazy ox-bow bend through the intense green of Gallats Meadow I stopped to sketch. A little farther I left the trail where it began to switch-back up to Colby Pass. Instead, I wandered up the meadows of the valley until the bottom roughened and began to climb into the box canyon at the head of the Kern-Kaweah. Here I turned up the ridge on the south side, and gained the heights below the mountain wall of the Great Western Divide just as the light failed, pitching my tent in the dark beside a tarn in a world of barren rock.

Rain came in with the night, and lightning stalked across the range. I lay awake, counting the seconds between flash and boom and worrying about the pass, waiting for dawn. Rising at first light, I packed in the clear air. Only a few clouds passed overhead as I climbed up to the notch, where I stopped to bask in morning sunshine. From my perch the west side looked steep and treacherous, especially where a slope of loose talus funneled through a vertical rock band. My stick broke among the rocks and in the chute I accidentally kicked a boulder loose and watched it bounce and fall hundreds of feet, praying there was no one climbing up beneath me. Finally I reached the big lake at the bottom, its emerald color inviting a swim. I wished for the sun to emerge from behind the clouds and it did just as I reached a smooth flat rock I had noticed from high above. I stripped and plunged into the icy water, quickly dressing as the sun disappeared again. Then I headed down the big green basin, studded with silver lakes and grey-granite boulders, out of the World of Foxtail Pines.